So here we are at the end of my son’s final year of high school.

He is unrecognisable as the pale blond boy, with a mother’s bad haircut, who entered Montessori as a three year old. His hair is darker, barber cut, his face longer and more bored. He seldom laughs, at least around his parents. Some times I glimpse the hair on his legs and it’s, “where did that little boy go?” I see the way he is with the dog and am relieved.

He has always been a reluctant school goer – despite changing from different styles of school, looking for the one with the best fit. Years of early education in Montessori, a few years in the traditional public school system and ending with six years of Catholic all boys school. All different, and yet all the same – approached with dreariness and shoulder-slumping.

I remember him making potions like the neighbour’s six year old does now. There was passion in potion making. Passion in spy make-believe, from the high vantage of the limestone wall. Passion kicking between the paper barks, in being Ablett and Bally. But no passion for school. School equated with work and work was something that adults complained endlessly about.

We wonder, as parents, if we could have done something better – his father laments he was too tough on him early. Did he ask too much of him? In moments of exasperation we did yell and holler louder than we wish. We have all wanted to rewind and take back those words that were blurted out at a child who appeared to be doing something just to make you boil over. I think of taking him to riding lessons at the Claremont show grounds – spurred on by his enthusiasm on a mule ride in the Grand Canyon. After a few lessons he began to hate it and cried in the car on the way there. And I drove on. I pleaded with him to finish the term. The teacher, still a girl, spent time on her mobile as he sat rigid, unsmiling on a barely moving pony, circling her.

I wish I had known as much as I do about dog training and behaviour when I could have influenced him more. How might I have been able to shape behaviour better? Maybe give him more choice? Now he seems cast adrift. I watch from the banks and know that ineffectual waving is all I can do. How do you wave to signify “take care”, “I love you”, “you can do this”, “I have your back.” The generic hand in the air is just that. Bye. He is too far out now for him to hear me. I am shrinking, as he slips away, over the breakers and becoming a barely seen blip on the shoreline of home.

He goes to an 18th birthday party when he is seventeen. He tells me it is in South Fremantle. Another parent will drive them and he waits for them on the driveway, whilst killing time shooting baskets. I don’t go out to check on the address with the parent who is driving, although I know this is something I should do. It is, no doubt, parenting 101. I don’t do it because I know my presence beside the car, leaning awkwardly in towards the driver, and perhaps saying something obtuse and embarrassing, will make him wince. He is waiting purposefully outside so as to avoid me speaking to and being seen by the other parent. I have given him money for the Uber home that he says his friend will order and that is all the information I have. My questions swirl about my head, but I have had my allotted two grunts today, and so further questioning will likely only irritate further.

It seems somewhat deserving that I have a son so abashed by me, as I was equally mortified in the presence of my mother. I would have mostly done anything to have the earth split in two and swallow her when she was with me. And yet she loved me with a fervour. Unerring. She seemed oblivious to the embarrassment she caused – effusive and ebullient with strangers, shop keepers and wait staff, anyone. And loud. I did, over time, get used to it, and even come to admire it, but it took me into my twenties and beyond to see that she did it because it was her. People gave her joy.

It has been said that when a parent or loved one dies the relationship keeps going and evolving. It doesn’t end because they’re no longer in the physical world. I think of my mother and feel a deep ache in the centre of my chest for the woman that loved me so intensely. I feel sorry that maybe she never saw how much she meant to me while she was still alive. My love for her has finally caught up to the love she had for me – if we were twin high divers we would hit the water together, in unison, and the entry would make the perfect ripple. People would applaud.

I swim laps in tepid summer pool and remember doing this pregnant. There are fires and droughts across the country. The internet is full of orange skies and burnt koalas. Climate change is real. Even rain forest can burn. I see mothers coming from the toddler pool with little damp limpets clinging to them. A baby sucks his mother’s bare shoulder. When I was pregnant, before I became too rotund, I was able to get into the pool unaided, by falling off the pool deck like a toppled bowling pin. Afterwards, I hauled myself out. Nearing the end of the pregnancy they had a mechanical hoist and I was freakishly lowered in and levitated out. Dead whale. While I swam, I meditated on the growing foetus – telling the little bean that their future would be bright, anything they wanted. I would repeat “you will be fit and healthy and happy” as I stroked up and down the pool. Now I enter via the ramp on an oversized water wheelchair, so plastic and hospital beige. I swim my laps, while the teenager still sleeps on. At completion a signalled-to life guard returns the wheelchair to the water and it is like being an astronaut manoeuvring it – my weightless body and jaunty legs, getting them in sync, before reaching the shallows and the vessel finds its own solidity and can be propelled up the ramp. More little toddlers dart in front of me and their mothers tell them to be careful. Careful of what? Me? What am I now? An old disabled woman, haphazard in the beige contraption.

I have not got enough information about the party. As I hear the car pull away I know this. When the boy/man’s father comes home and I explain why I don’t have this information I know it sounds weak and feeble. I am feeling weak and feeble. Feeble mother. How did offending this boy become something I am so reluctant to do?

We watch an episode of Chernobyl, like the middle aged people we are. We watch the flesh melt off the radiation affected humans and a child born die within four hours of her birth. We watch the conscripted soldiers shoot the abandoned pets, who eye them soulfully, and then tip them into deep pits and pour concrete over their corpses. We see bravery and stupidity. Boron and graphite take on new meaning. TV ads telling of the 16 types of cancer you can get from sugary drinks from the toxic fat in your abdomen need to be muted as I take a glance down at my own waist line. Like the hair on my son’s legs I don’t know how my own belly came to be there.

I think about my own going out at seventeen. My parents watching the Onedin Line. How my mother loved Peter Gilmore. I wonder what my parents knew of where I was going or what I would be doing and when I would be home. Of the contraceptive pill in the drawer beside my bed. They could not ring to check on me. I could phone the boy/man now if I wanted. Did our parents lie in their beds wondering? Did they worry about girls in cars with boys? Did they know that we chugged back cans of asphalt black Kalgoorlie Stout till the Broadway’s bathroom walls swayed in towards our brows?

I go to bed, but not to sleep. I think of alcohol being consumed by others and someone punching him hard in the face. I think of him perhaps wanting to come home but having to wait for his friend, the one with the Uber App, to be ready to leave. Will he be cold? I should have given him more instructions. Just the other day he couldn’t figure out how to open the shoe polish tin and asked me to do it for him. Have I done too much? His father says I have. So there we have it – a mother who has done too much and a father who has been too hard. The push and the pull.

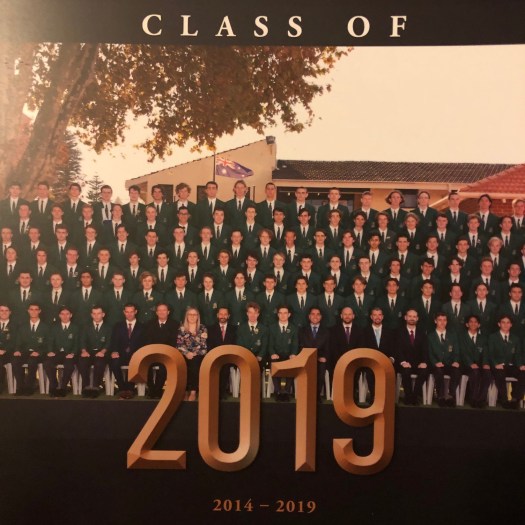

At the assembly we sit close to the rows of Year 12 boys. They are spotty faced and embarrassed by the attention of their parents. Blazers are poor fitting and boys have haircuts called curtains that would displease the dapper principal. The Mark Knopfler track, Going Home starts and the year sevens get to their feet and silently move into position. Parents line the gym’s perimeter and are armed with their mobiles high in the air to catch the moment when their year 12 sons stand, the drums begin and they proceed out embraced by applause. Some mothers shed tears and wipe their eyes with tissues. I see the lacquered pink toenails of the woman beside me and her garish platform sandals. Is her son embarrassed by this?

I post the videos of the last school assembly and a picture of a him and a friend taken when they come back to the house, before going to the beach. His blazer is too short in the arms and too narrow across the back, but he has refused to buy a new one, with so little of school time left. His friend’s blazer is awkwardly large. The boy/man is cross with me for having posted and says I should ask his permission. But I refuse to take it down. It is my memory. It is for me that I post it. I have come through this too. It is a graduation from school volunteering, of sitting and applauding, of listening to prayers and not saying the Amen when others do.

From feeling the pang of leaving a small boy at a classroom entrance. to hearing he has been silent the whole day long. to watching as he trails behind the other lonely child. to wondering why he can’t read when others can and have him reveal that the class helper is on her phone when he reads aloud to her. to wanting to bat away another small child who has made yours not want to show his work at corroborree. to hearing that the male teacher yells at children who are only 10 years of age. to not getting a place in a special program and having to tell him so he runs away and hides in a wardrobe. to hear him say “but what about my career?” to waking up at night saying he is being attacked by numbers when he is in grade seven. to seeing him stand on the sideline and wait endlessly to be substituted in. to hearing he is delightful in class and always asks questions when he is unsure of what to do. to hearing that the deputy principal says he is the epitome of a CBC gentleman. all these pangs criss cross a mother’s heart. little stitches in precious thread.

The party is on the beach and they make a fire. There are girls and alcohol. He says he drinks water. I wonder how hard that might have been. I can’t tell. He gets home before midnight and can hear a murmur of conversation between him and his father who has stayed up. I have not slept. I have turned my phone off silent, just in case. I think next time I will ask for an address and give him a curfew.